Stefanie Onder and Diego Herrera

Assistant Professor, American University's School of International Service; Environmental Economist, World Bank’s Global Department for the Environment

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is becoming widely recognized as an insufficient measure of economic progress and national “success.” Since GDP is nearly universally available and comparable across countries, it is extensively used as a benchmarking and reference statistic even for purposes for which it was not designed. GDP measures the level of domestic productive activity, but it ignores the costs of this growth in terms of, for example, environmental degradation that occurs in the process of production. Sir Partha Dasgupta likened this to a soccer team that only measures success as goals for and ignores goals against.

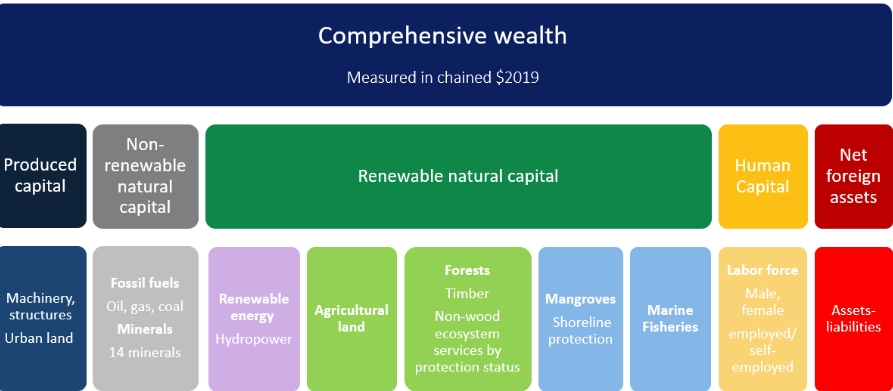

Whether economic progress is sustainable can be measured by how real wealth per capita is changing, as this represents changes in the potential for future growth. Wealth, in this context, encompasses the value of all the assets of a nation that support economic production, such as its factories and roads (produced capital), forests, fish stocks, and fossil fuel reserves (natural capital), labor force (human capital), and net foreign assets (see Figure 1). As long as real wealth per capita does not decline, future generations will have at least the same opportunities as the current generation, suggesting that development may be sustainable.

Figure 1: The CWON wealth accounts (2024 release)

However, while all countries produce GDP estimates, few measure real wealth; a gap that the World Bank’s The Changing Wealth of Nations (CWON) fills (World Bank, 2024). CWON is one of the pioneering efforts in measuring wealth, producing the most comprehensive, publicly accessible, and reproducible wealth database currently available. These monetary estimates draw on internationally endorsed concepts and valuation principles from the System of National Accounts and System of Environmental Economic Accounting. This ensures that CWON’s wealth measure is methodologically rigorous and comparable to other metrics of economic progress like GDP.

The recently published 5th edition implements a new approach for measuring changes in real wealth per capita, which better captures the extent to which assets are accumulated or depleted, or are becoming more or less scarce. For example, real wealth per capita will increase if more workers enter the labor force or if the same workers upgrade their skills, if forests grow, or new commercially recoverable minerals are discovered. However, it will decline if fish stocks are overfished, machinery degrades, or the reserves of fossil fuels are depleted or become commercially unexploitable.

By monitoring per capita trends in real GDP and real wealth together, it is then possible to assess whether growth in GDP is achieved by growing the productive base of the economy or by shrinking it. The report finds that globally real wealth per capita has increased by about 21 percent between 1995 and 2020, whilst real GDP per capita increased by about 50 percent over the same period. However, this global average masks differences across regions and countries. For example, growth in real wealth per capita relative to 1995 is particularly pronounced for the Middle East and North Africa region (97 percent increase) and Latin America and the Caribbean (66 percent increase) due to substantial rises in human and produced capital. However, out of the 151 countries in the CWON sample, 27 countries have experienced declines or stagnation in real wealth per capita, most notably low-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa or in fragile and conflict-affected states.

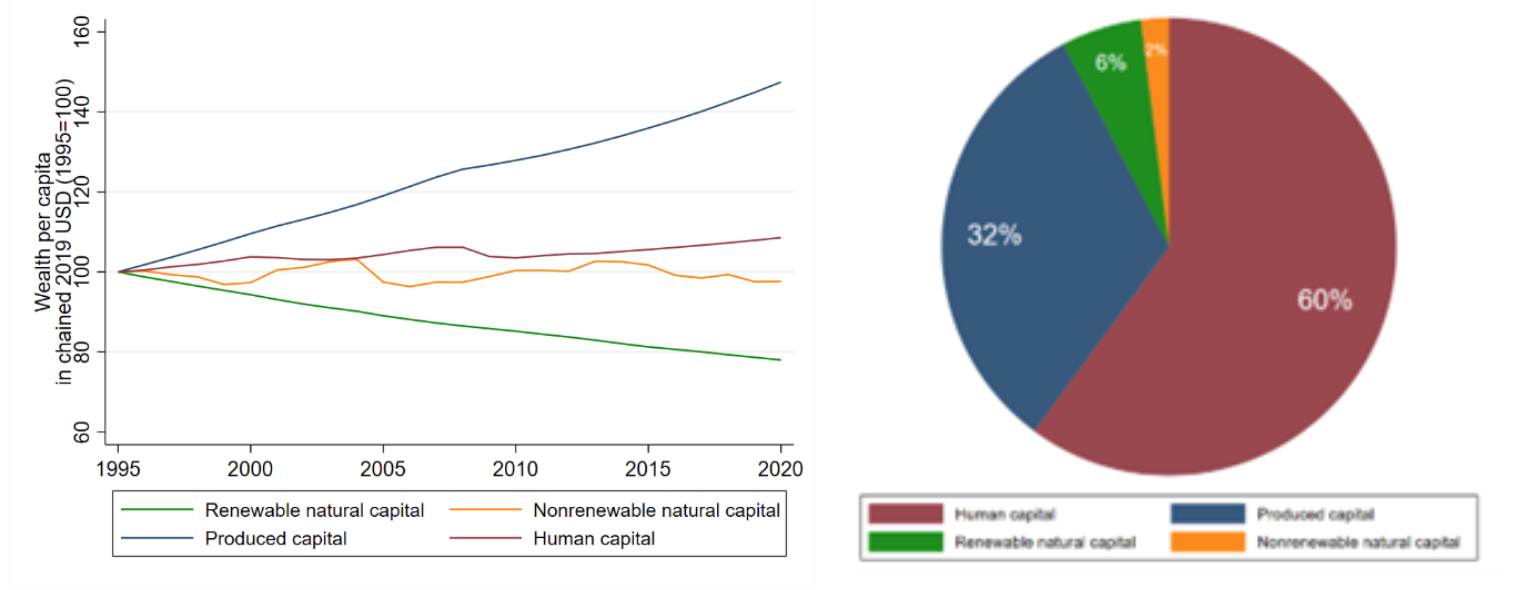

Trends in real wealth per capita are ultimately driven by changes in the underlying assets, with contrasting trends across different categories. Human capital, the most important asset for countries (Figure 2b), has increased by about nine percent per capita compared to 1995, due to higher labor force participation and educational attainment (Figure 2a). Rapid urbanization and industrialization have also expanded in produced capital wealth, which increased by 47 percent per capita between 1995-2020. Nonrenewable natural assets, on the other hand, have slightly declined over the same period. This is the most volatile category, where years of growth are followed by sudden losses of value, partly driven by changes due to new discoveries and technological innovations as well as price fluctuations. Meanwhile, renewable natural capital, which should be able to regenerate itself if managed sustainably, has declined by more than 20 percent per capita over the past quarter of a century; a decline that can be observed across all regions and income groups.

Left: Figure 2a: Trends in global wealth per capita, by asset category, 1995-2020 (1995=100). Right: Figure 2b: Nominal wealth shares, by asset category, 2020

Wealth measures such as CWON’s provide an important step towards developing metrics beyond GDP, which can be used to assess sustainability trends across countries and over time. However, these estimates also have their shortcomings. For instance, they reflect only the current policy environment and market expectations and are blind to the possible impacts of future policy actions or changes in market conditions due to, for example, climate change. To explore policy scenarios, researchers can use the CWON input data and code to change various assumptions in modelling exercises to derive their own wealth estimates. For example, this data can be used to explore how policies aimed at promoting a circular economy will affect the asset portfolio, and ultimately, wealth of a country. Such policies would change the real value of individual assets, as an economy becomes more efficient at using its resources. They could also change the availability of given resources, as a more sustainable use of, e.g., renewable natural capital is encouraged. By changing assumptions about future asset values and volumes, policy-contingent wealth estimates can be estimated and compared to the baseline CWON estimates. Such an analysis would then reveal how overall wealth and the composition of the asset portfolio would change under different circular economy scenarios.

References

World Bank. The Changing Wealth of Nations 2024: Revisiting the Measurement of Comprehensive Wealth (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099100824155021548/P17844617dfe6e0241ad25120b1320904c2