Gabriela Vidad, Stephon T. Smith, Amaris Norwood, Zoë Mattioli, and Lukas Adamski

MS in Sustainability Management Students, Kogod School of Business

Background

About the Project

Essential parts of our diet are in danger due to climate change. Specialty crops, encompassing fruits, vegetables, and nuts have an advantage over commodity crops due to their high market potential and nutritional value. California plays a pivotal role in the production of specialty crops, contributing to over one-third of vegetables and two-thirds of fruits and nuts in the United States (Kurnik 1). However, the concentration of these crops in California poses a significant cluster risk as climate patterns shift. The World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Next California Project addresses climate change risks in the agricultural industry by exploring the relocation of specialty crops to the Mid-Mississippi Delta, which could benefit economically and has the potential to sustainably grow strawberries, walnuts, watermelon, lettuce, peaches, and persimmons.

We strive to answer the question, “How do we finance specialty crop infrastructure to promote economic development in the Mid-Mississippi Delta?” This project focuses on exploring innovative financial vehicles that can support the development of specialty crop infrastructure and operations, with the goal of making the Mid-Mississippi Delta region an even more robust agricultural center for new and existing farmers. Throughout this process, we remain committed to incorporating principles of environmental sustainability and social equity, employing innovative strategies to reduce costs and enhance long-term profitability.

Environmental and Equity Considerations

The Mid-Mississippi Delta region is not immune to the effects of climate change. In 2016, the EPA reported that this region—comprised of the states Arkansas, Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi—would be affected by more extreme heat, drought, and flooding. With this in mind, farming methods that center environmental sustainability should be implemented while converting commodity cropland to specialty cropland. Any form of single-crop agriculture and excess use of fertilizers can perpetuate soil degradation (Simpkins; Bogužas). If crop rotations and multi-crop growing of specialty crops are feasible, this could help revitalize the soil and decrease negative health impacts of excess soil use on surrounding communities where many are already suffering from poor health (Miller and Woods).

The history of the region is riddled with the displacement of Indigenous People and the enslavement of African Americans. Today, the agriculture industry has made it difficult for Black farmers to maintain and afford their own land—many work for wealthier landowners (Freshour and Williams). Much of the food produced in the region is exported, leaving surrounding communities with a lack of access to healthy food (Miller and Woods). Both the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, the only recognized federal tribe in the region, and Black farmers via the Mississippi Association of Cooperatives have turned to co-ops to reclaim their agricultural roots in a way that avoids exploitation, keeps wealth in the region, and feeds their communities (Greenfield; Miller and Woods). Although these co-ops provide native and specialty crops on a hyperlocal scale, we will adopt their social and environmental priorities in the development of the specialty crop industry in the region.

Key Learnings

Investment and Trading Vehicle

The first step in funding specialty crop infrastructure for the project will include a stakeholder mapping process that identifies a small group of motivated farmers to participate in an investment vehicle. Although investment amounts are fluid and uncertain, specialty crops will need initial investments for agriculture infrastructure, e.g., processing and freezing plants. Over time, it will be necessary to generate cash flow to pay back the debt of initial investments. For this, we analyzed different finance structures that support a successful provision of capital.

As the basis for capital provision, we propose to create a legal structure as a financing vehicle. This vehicle can invest in the needed agriculture infrastructure for the project while continuing to operate and maintain these assets. After the infrastructure is built, farmers or trading co-ops can rent the infrastructure for their production.

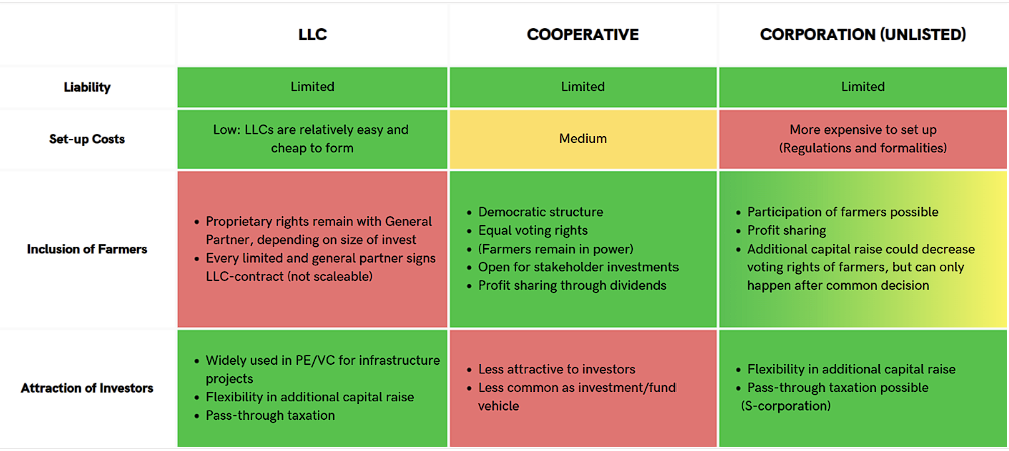

We compared Limited Liability Companies (LLCs), Cooperatives, and Corporations to determine the most effective legal form to raise capital while simultaneously keeping farmers in power (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Advantages and disadvantages of LLCs, Cooperatives, and Corporations as finance vehicles

While cooperatives are less often used than LLCs to raise capital by private equity and venture capital funds, cooperatives can similarly collect capital from impact investors, issue bonds, and collect bank loans. The cooperative solution is especially charming due to the democratic ownership structure; irrespective of the amount of invested capital, every equity investor has only one vote in the common decision-making process. Thus, a cooperative model would keep farmers in power and enable them to participate in business decisions. Simultaneously, other stakeholders such as citizens, governments, or employees can invest and benefit from future dividends as well, and thus increase the total raised equity.

In scenarios of high financial pressure, like a pending insolvency, it can be important to quickly raise capital. Investors expect a tradeoff in the form of ownership rights in return for the investment. But since the one vote per person rule intentionally prohibits this, cooperatives are less attractive to investors.

Corporations, on the other hand, can combine the advantages of investor attraction and democratic structure. As an unlisted corporation, shares are not publicly traded, and new investors are accepted by the current investors. This way, dilution of farmer shares can be prohibited, and the power remains with the farmers. In a critical financial situation, external investors may invest in exchange for ownership rights. This would lead to dilution but would save the project.

Since an unlisted corporation can both attract new investors and keep farmers in power unlike the LLC and cooperative, our recommendation is to move forward with this legal form for the investment vehicle.

Crowdfunding: an innovative alternative to raise subordinated debt.

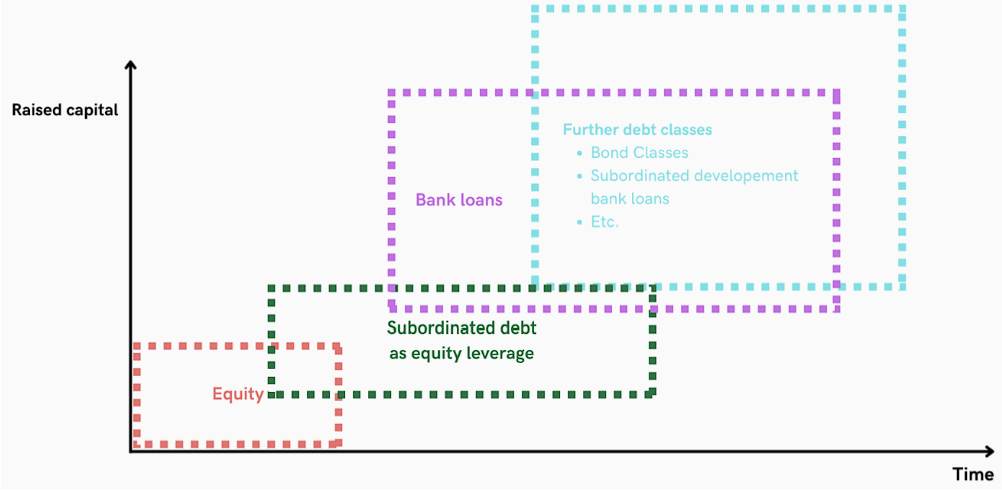

The following graphic illustrates the potential financing strategy for the agriculture infrastructure with evolving project growth:

Figure 2: Structure of Equity and Liability Over Time (Illustration inspired by Hoppe 281)

In the beginning of the project, risk capital like equity and subordinated debt is needed as a basis to collect further debt to build the initial infrastructure. Equity investors usually receive proprietary and voting rights. This means a reduction of voting rights for farmers. To avoid this, we strive to utilize innovative financing solutions focusing on subordinated debt to keep farmers in power. We propose to collect capital using crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding can be structured as subordinated debt. This capital buffer enables further financing sourcing. Since subordinated debt is not connected with voting rights, all rights remain with the owner of the company. Today, academic literature for startup financing names crowdfunding as a relevant source to raise capital for early-stage companies (e.g. Hoppe 3), which leads us to see great potential in crowdfunding for this project.

Figure 3: SWOT-Analysis of Crowdfunding to Raise Subordinated Debt

Crowdfunding in the US: Strategic Market Analysis

Let’s take a closer look at the crowdfunding landscape as it would pertain to The Next California Project. Our analysis of the US market analysis indicates that many crowdfunding campaigns collect $30,000 to $30,000,000, with many projects collecting over $1 million.

For retail clients, crowdfunding investments are often connected to personal preferences and emotional connection to projects. For example, 72 percent of consumers are concerned about climate change (Bell et al.). To that point, global warming is the largest existential societal fear (Edelman Trust Barometer 7). An investment opportunity for climate resiliency, such as a sustainable agriculture initiative, could create an emotional impact on retail investors who feel an urgency and need to act. Thus, we see a great opportunity for utilizing crowdfunding for this project.

Based on our market research, we determined a potential goal to raise $300,000 with one crowdfunding campaign. This campaign could be repeated periodically to raise further capital.

Discount on Cost of Capital

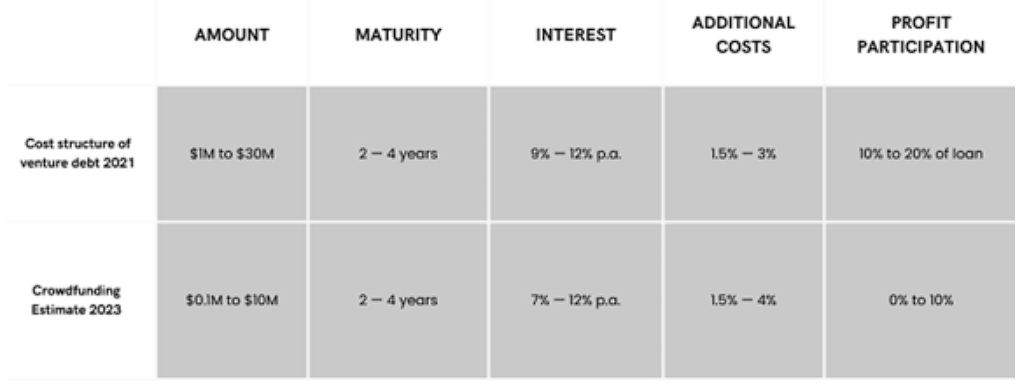

Based on our market research, we determine the following cost structure for a crowdfunding project in 2023 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Cost structure of Venture Debt 2021 and Crowdfunding estimates for June 2023, own (Data from Hoppe 224).

The interest on debt depends on changes in risk free interest (cf. US treasury bonds) and project-related risks. Even though the yield of US treasury bonds increased significantly between 2021 and 2023, the 2023 interests of crowdfunding projects are still significantly lower than comparable risky investments (venture debt 2021 + increase in risk free rate), as highlighted in Figure 4 (Rennison and Simonetti). We explain this is due to an information asymmetry between professional investors and retail investors. Professional investors are more aware of changes in market interest and demand higher interest. Retail investors do not have the same market insight and knowledge. Thus, a discount on interest can be reached through retail-oriented crowdfunding.

In summary, subordinated debt is needed to access further capital for financing the agriculture infrastructure while keeping farmers in power. For this, we see great potential in crowdfunding to raise subordinated debt for the project.

Application of Key Learnings

For this next section of the report, we utilize our key learnings to develop two financial solutions, the Investment Vehicle and Trading Vehicle, to secure funding for The Next California Project.

Investment Vehicle: Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund

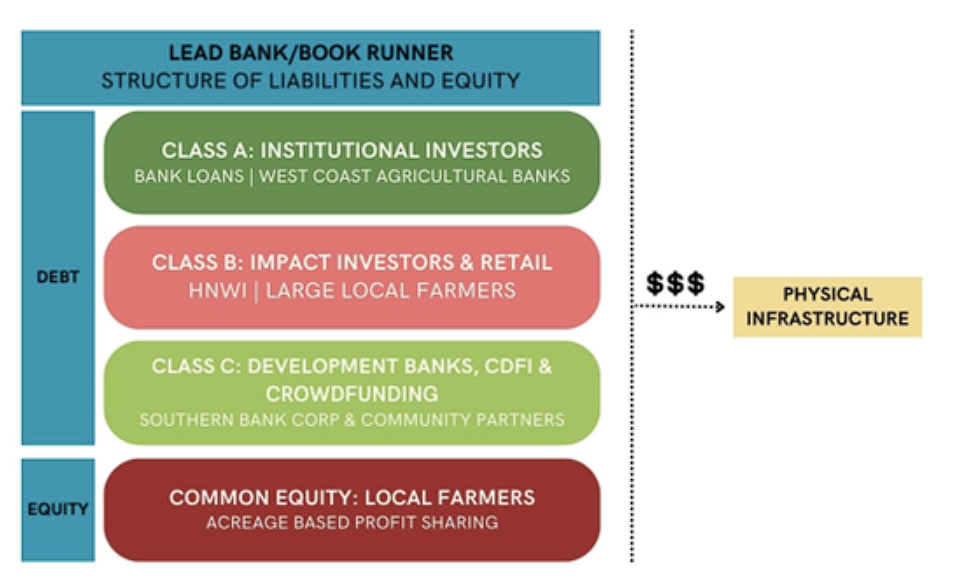

The Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund is strategically crafted to appeal to investors with diverse priorities and varying risk tolerance levels. This is achieved through the issuance of different tranches of debt, each specifically tailored to target distinct investor types.

Figure 5: Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund

- Class A investors are traditional funding sources seeking a sizable return for a larger injection of capital. We recommend that in addition to the local and regional banks of the Mid-Delta that the fund targets large West Coast agricultural financial institutions who are interested in investing as a portfolio hedge against physical and transition climate risks. The Mid-Delta region has historically been less affected by extreme weather events such as hurricanes and droughts compared to other agricultural regions in the country. This can provide a diversification benefit to West Coast agricultural financial institutions that may have increased exposure to such risks.

- Class B investors are impact investors who are interested in more than just financial returns. They are likely to be large local farmers who want diversified exposure to the "Next California" transition but are not particularly interested in transitioning from the commodity row crop practices. These investors may be willing to take on more risk than Class A investors, as they are motivated by both financial, social and environmental impact returns. The fund may also offer a higher interest rate to Class B investors if they fail to meet certain objectives, which indicates that the fund seeks to incentivize social impact through performance-based returns.

- Class C is a tranche for any restricted money tailored to infrastructure, marketing, and farmer education projects. This tranche may be attractive to investors who are interested in philanthropy or impact investing, as it allows them to support specific projects that align with their values. The fund will also accept Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) capital, which takes on the highest risk in the structure and can be used earlier in the pilot program. The fund's equity component is for any unrestricted grant money the fund receives and seeks to address historic inequities in the region for Black and Indigenous farmers. The fund will provide these farmers with a stake in the transition of the region through a creative profit-sharing model and voting rights on any future development in the region.

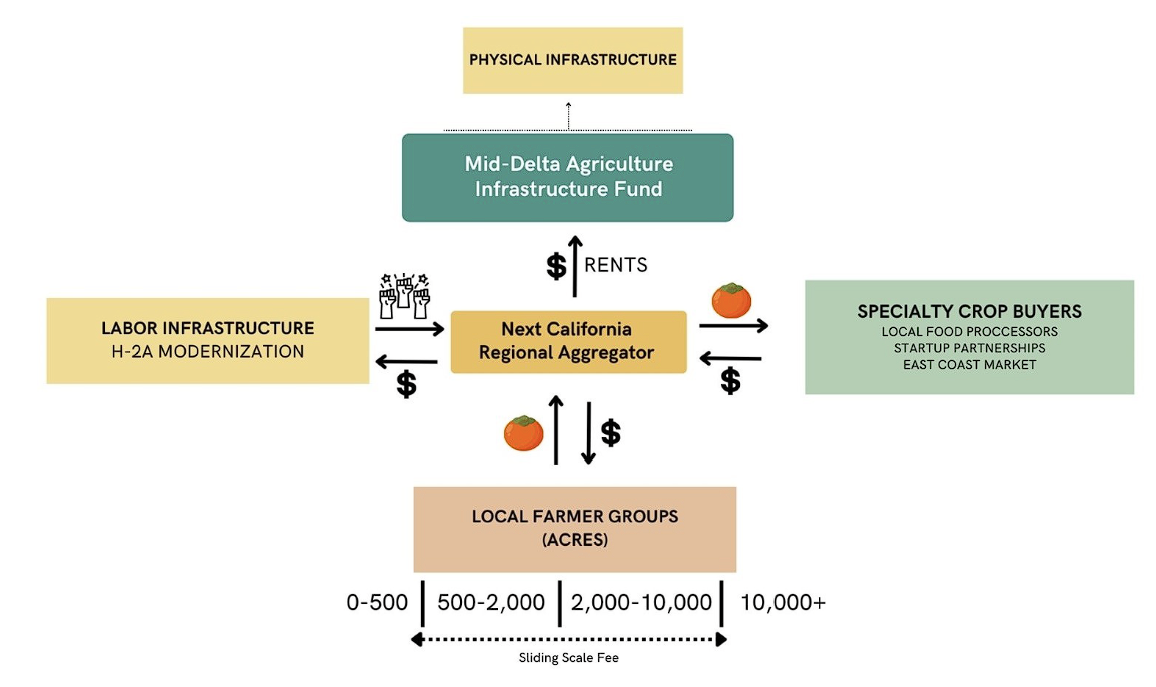

Trading Vehicle: Next California Regional Aggregator Cooperative

The purpose of this vehicle is to harness the collective bargaining power of the region's specialty crop growers by aggregating their produce and the infrastructure needed to bring them to market. The strategy is aimed at increasing the profitability of specialty crops for farmers of all sizes and investors in the fund, while also providing pricing stability for regional and East Coast consumers who currently depend on California suppliers. This will be accomplished through the formation of a cooperative entity called the Next California Regional Aggregator Cooperative.

Figure 6: Next California Regional Aggregator Cooperative

Aggregating Specialty Crops for Regional Collective Bargaining Power

The proposed strategy employs funding from the Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund to secure infrastructure for chosen specialty crops, enhancing regional economies of scale in production, processing, and distribution. Investors gain profits through Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund lease payments, while farmers benefit from reduced costs and higher prices. Success hinges on key partners like Cushman & Wakefield and Commercial Advisors (CW|CA), tasked with securing land for infrastructure, managed by the Next California Regional Aggregator Cooperative. This structure shields the investment fund from legal issues, offering liability protection. The Aggregator Service charges fees to farmers based on farm size, ensuring fair market access and preventing monopolization. Using the service grants farmers stable prices through large forward contracts, equalizing bargaining power regardless of farm size.

Market Creation

The USDA Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) aims to foster domestic and international marketing for US food, fiber, and specialty crop producers. AMS would provide data to the aggregator service for specialty crop pricing and competitor origins on the East Coast. This data would inform the aggregator service's purchasing decisions, ensuring fair prices for both farmers and buyers.

The Common Market aids in securing initial contracts with local food service providers, establishing stable demand crucial for attracting investors. Partnering with Arkansas Grown, a program similar to The Common Market, would enhance market creation efforts by connecting producers and consumers, offering education, training, and networking opportunities.

Crunchbase proves invaluable for researching food and beverage companies in the Mid-Delta region and overall Southern US, offering insights in a range from startups to Fortune 1000. Using Crunchbase, we’ve identified potential partners like Twelve Oaks Catering, which was acquired by Riveter Capital in March 2023 and underscores a growing interest in firms prioritizing healthy meals. Other startups like Epic Sales Partners, Main Squeeze Juice, Blenders & Bowls, Olyra, I Love Juice Bar, and Globowl offer diverse products. While not exhaustive, these companies could become future customers for The Next California based on specified criteria.

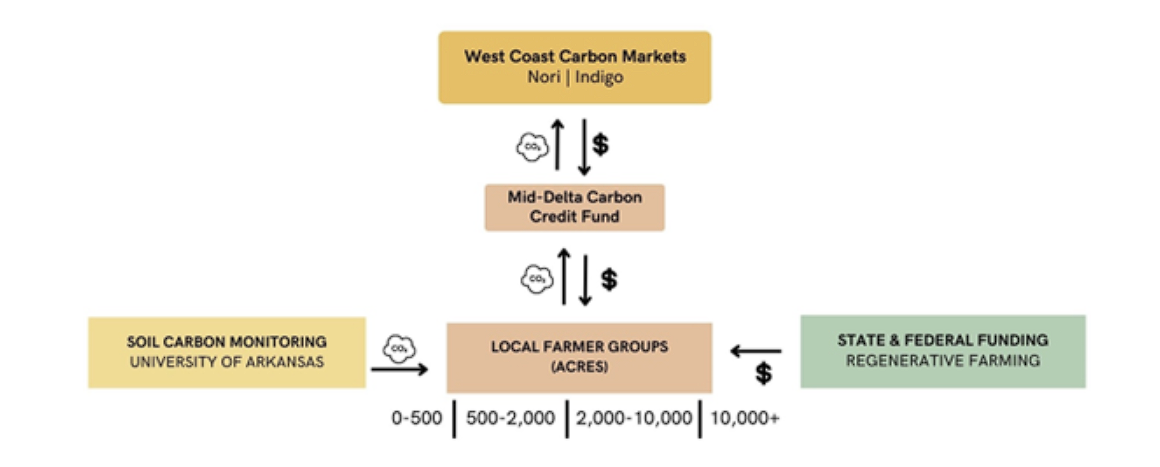

Trading Vehicle: Mid-Delta Carbon Credit Fund

This vehicle proposes that farmers can capitalize on the low-carbon transition to earn additional income by reducing their carbon emissions and sequestering carbon in their soil as they transition to specialty crop farming.

Figure 7: Mid-Delta Carbon Credit Fund

Capitalize on the Low-Carbon Transition to Earn Additional Income

By implementing practices to track CO2 emissions and sequestration, farmers can earn a possible $15 per metric ton (mt) per acre per year. This additional revenue can also be earned prior to the full adoption of specialty crop farming as the introduction of regenerative farming techniques is an independent but collaborative strategy—this can be used to supplement the income of farmers that are not yet financially able to join the regional aggregator service. This section outlines the process to start funding for soil carbon monitoring to set up a baseline and viability of potential farms and key partners who can assist in the process.

Funding for Soil Carbon Monitoring

To begin the process, farmers need funding for soil carbon monitoring to set up a baseline and viability of potential farms. The University of Arkansas scientists can be key partners in this process, providing data tracking for $4,000 per year (industry average for this service). By implementing tracking of CO2 emission and sequestration, farmers can earn a possible $15 per mt per acre per year.

Federal and State Funding for Regenerative Farming

Federal and state funding can be applied for on behalf of farms for regenerative farming implementation. It is unclear yet whether funding can be added to Class C tranche of the Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund, or if it must be handed to farmers directly. Some state programs currently offer $15 per acre, which indicates additional research opportunities.

Carbon Credits in West Coast Carbon Markets

The majority of CO2 credits can be sold in West Coast Carbon Markets, which will rise over time as transition risk for industry and non-industry participants increase over time. Key partners, such as Nori and Indigo, can assist in this process. Nori and Indigo are two companies that specialize in the carbon offset market and provide services related to carbon credits. Nori is a company that helps farmers and landowners get paid for removing CO2 from the atmosphere by verifying and selling carbon offsets. They do this through a blockchain-based marketplace that connects buyers and sellers of carbon credits. Nori verifies the carbon reduction and removal efforts of farmers, and then allows them to sell those carbon credits to buyers who want to offset their own carbon emissions. Indigo is a company that helps farmers improve their soil health and sequester carbon by providing them with the technology, data, and financial incentives to do so. Indigo offers a platform called the Terraton Initiative, which aims to remove one trillion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere by incentivizing farmers to transition to regenerative agriculture practices. The company works with farmers to implement sustainable practices that can help to rebuild soil health and sequester carbon, while also providing buyers with a way to offset their carbon emissions by purchasing verified carbon credits.

Potential Issues with Investment and Financial Vehicles

Businesses operating across state lines face varying laws and regulations, particularly in the Mid-Mississippi Delta region, where unique state laws govern operations. Divergent tax rates and business entity registration requirements add complexity. To optimize legal entity liability protection and minimize tax burdens, seeking guidance from a lawyer and accountant is crucial. They can assist in selecting the most advantageous legal structure and leveraging state-specific tax incentives.

As an example, the carbon monitoring tools explored above often cater to West Coast and some East Coast markets, posing challenges for Mid-Mississippi Delta farmers. To address this, some solutions could include:

- Research: Explore firms developing carbon monitoring tools tailored to the region's topography, soil, and climate.

- Adaptation: Modify existing tools by incorporating regional data and refining algorithms based on local farmer feedback.

- Collaboration: Partner with local universities, research institutions, and agricultural offices to conduct region-specific carbon sequestration research. The University of Arkansas professors could offer valuable expertise.

- Advocacy: Advocate for policymakers to allocate funding and incentives for the development and adoption of carbon monitoring tools specifically designed for the Mississippi Delta region.

Pro Forma Financials

We created a step-by-step financial model that outlines The Next California pilot and projects the breakeven point for farmers transitioning 100 acres of farmland to specialty crop, using permissions as an example. Although the assumptions used in the model are an aggregation of various data sets and may not be 100% accurate, it provides an idea of what the pilot program's results could look like. It is important to note that this is just an estimate, and actual results may vary.

It would take approximately 2.85 years to break even if 1 acre can yield 6.95 tons of persimmons and they are sold for $1.59 per pound. This, however, does not account for the actual interest rate that must be captured for the fund investors through infrastructure lease payments. It would take approximately 3 years to break even with the initial investment of $6,305,000 with total interest paid of $971,862.18 over the three years. This also assumes a standardized risk-free rate of return (Current US Treasury 10Y Yield at 3.63%) across the three tranches in the Mid-Delta Agriculture Infrastructure Fund, which would not be the case. Also, persimmon trees propagated from seeds begin producing a crop in about four to nine years, while grafted trees can begin fruiting three years after planting. This can extend the breakeven point from 3 years to a range of 7 years to 12 years.

To calculate the breakeven point for each state, we need to know the yield per acre and the cost per acre. We know that 1 acre can yield 6.95 tons of persimmons, which can be sold for $22,101 ($1.59 per pound x 13,900 pounds per acre). We can calculate the total farm production expenses per acre by dividing the total farm production expenses per farm by the average size of farms in each state. We can then multiply this percentage by the total cost per acre to get the cost per acre for each state.

Missouri: ($68,052.21 / $22,101) + 4 years to 9 years = 7.07 to 12.07 years

Tennessee: ($77,702.39 / $22,101) + 4 years to 9 years = 6.51 to 12.51 years

Arkansas: ($69,263.16 / $22,101) + 4 years to 9 years = 6.13 to 12.13 years

To calculate the change in breakeven for each state if the farmer also sells carbon credits, we need to calculate the additional revenue generated by selling carbon credits for each state. Assuming the farmer uses the entire average amount of farmland for selling carbon credits, the additional revenue from selling carbon credits per acre per year can be calculated as follows:

Additional Revenue = Price per metric ton of CO2 x Carbon sequestered per acre x Number of metric tons of CO2 sequestered per acre

To calculate the new breakeven point for each state, we need to add the additional revenue from selling carbon credits per acre per year to the revenue per acre from selling persimmons and recalculate the breakeven time. However, this calculation can be challenging due to the need to determine the Carbon sequestered per acre and Number of metric tons of CO2 sequestered per acre. The Web Soil Survey can be a reliable source, but we found that the data is only available for Areas of Interest smaller than 100,000 acres. It would be possible to estimate selling carbon credits on a farm-by-farm basis.

Looking Forward

- We encourage WWF’s Next California project to use our findings in the development and implementation of the future pilot program. The pilot program should begin by targeting farmers in the Mid-Delta region of Arkansas that align with our environmental and equity considerations.

- It will be important to determine initial conditions (e.g., funding needed, equity) and set up an efficient legal structure for the investment and trading vehicle. Our recommendation is to use an unlisted corporation for the legal structure, and to explore crowdfunding for raising capital.

- A small group of farmers should be onboarded for soil monitoring and CO2 reporting to build a foundation for the Mid-Delta Carbon Credit Fund.

- Lastly, The Next California Project should actively and continuously adapt finance strategies with dynamic project growth. Stakeholder engagement, such as local communities, markets, and policymakers, will be essential for maximizing the longevity of this impressive agriculture initiative.

Citations

2023 Edelman Trust Barometer. Edelman, 18 Jan. 2023, www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2023-03/2023%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report%20FINAL.pdf.

Bell, James, et al. “In Response to Climate Change, Citizens in Advanced Economies Are Willing to Alter How They Live and Work.” Pew Research Center, 21 Sept. 2021, www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/09/14/in-response-to-climate-change-citizens-in-advanced-economies-are-willing-to-alter-how-they-live-and-work/.

Bogužas, Vaclovas, et al. “The Effect of Monoculture, Crop Rotation Combinations, and Continuous Bare Fallow on Soil CO2 Emissions, Earthworms, and Productivity of Winter Rye after a 50-Year Period.” Plants, vol. 11, no. 3. 2022, pp. 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11030431

Cosier, Susan. “For Thousands of Years, Indigenous Tribes Have Been Planting for the Future.” NRDC, 30 Nov. 2021, www.nrdc.org/stories/thousands-years-indigenous-tribes-have-been-planting-future.

Freshour, Carrie, and Brian Williams. “Toward “Total Freedom”: Black Ecologies of Land, Labor, and Livelihoods in the Mississippi Delta.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, vol. 113, no. 7. 2022, pp. 1563-1572. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2103501

Greenfield, Nicole. “A Mississippi Tribe Is Growing Its Own Organic Movement.” NRDC, 16 May 2022, www.nrdc.org/stories/mississippi-tribe-growing-its-own-organic-movement.

Hoppe, C. (2021). Praxishandbuch Finanzierung von Innovationen. Springer Gabler.

Kurnik, Julia. “The Next California Phase 1: Investigating Potential in the Mid-Mississippi Delta River Region.” WWF, 2020, files.worldwildlife.org/wwfcmsprod/files/Publication/file/34t96wfe6b_The_Next_California_Phase_1_Report_02_27_20.pdf.

Miller, Julian D., and LeBroderick A. Woods. “Black Co-Op Farms: Building a Worker Strategy in Mississippi.” NPQ, 15 Dec. 2022, nonprofitquarterly.org/black-co-op-farms-building-a-worker-strategy-in-mississippi/.

Rennison, Joe, and Isabella Simonetti. “Relentless Rise in Interest Rates Looms over Another Volatile Week for Markets.” The New York Times, 21 Oct. 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/10/21/business/bonds-interest-rates-stocks.html.

Simpkins, Kelsey. “Soil Degradation Costs U.S. Corn Farmers a Half-Billion Dollars Every Year.” CU Boulder Today, University of Colorado Boulder, 12 Jan. 2021, www.colorado.edu/today/2021/01/12/soil-degradation-costs-us-corn-farmers-half-billion-dollars-every-year.